. Birds in their relations to man; a manual of economic ornithology for the United States and Canada . rd usually does harmrather than good in eating a parasite of an injurious phy-tophagous insect. Nothing has been said in regard to those parasites uponparasites which are called the secondary or hyper-parasitesof noxious insects. Our knowledge of the precise biologicalrelations of these is limited. On general principles it is prob-able that when a bird eats one of these it is at least as likelyto be doing man a benefit as an injury.1 1 For an account of the relations between hymenopterous par

Image details

Contributor:

Reading Room 2020 / Alamy Stock PhotoImage ID:

2CP1P7WFile size:

7.1 MB (367.6 KB Compressed download)Releases:

Model - no | Property - noDo I need a release?Dimensions:

1648 x 1516 px | 27.9 x 25.7 cm | 11 x 10.1 inches | 150dpiMore information:

This image could have imperfections as it’s either historical or reportage.

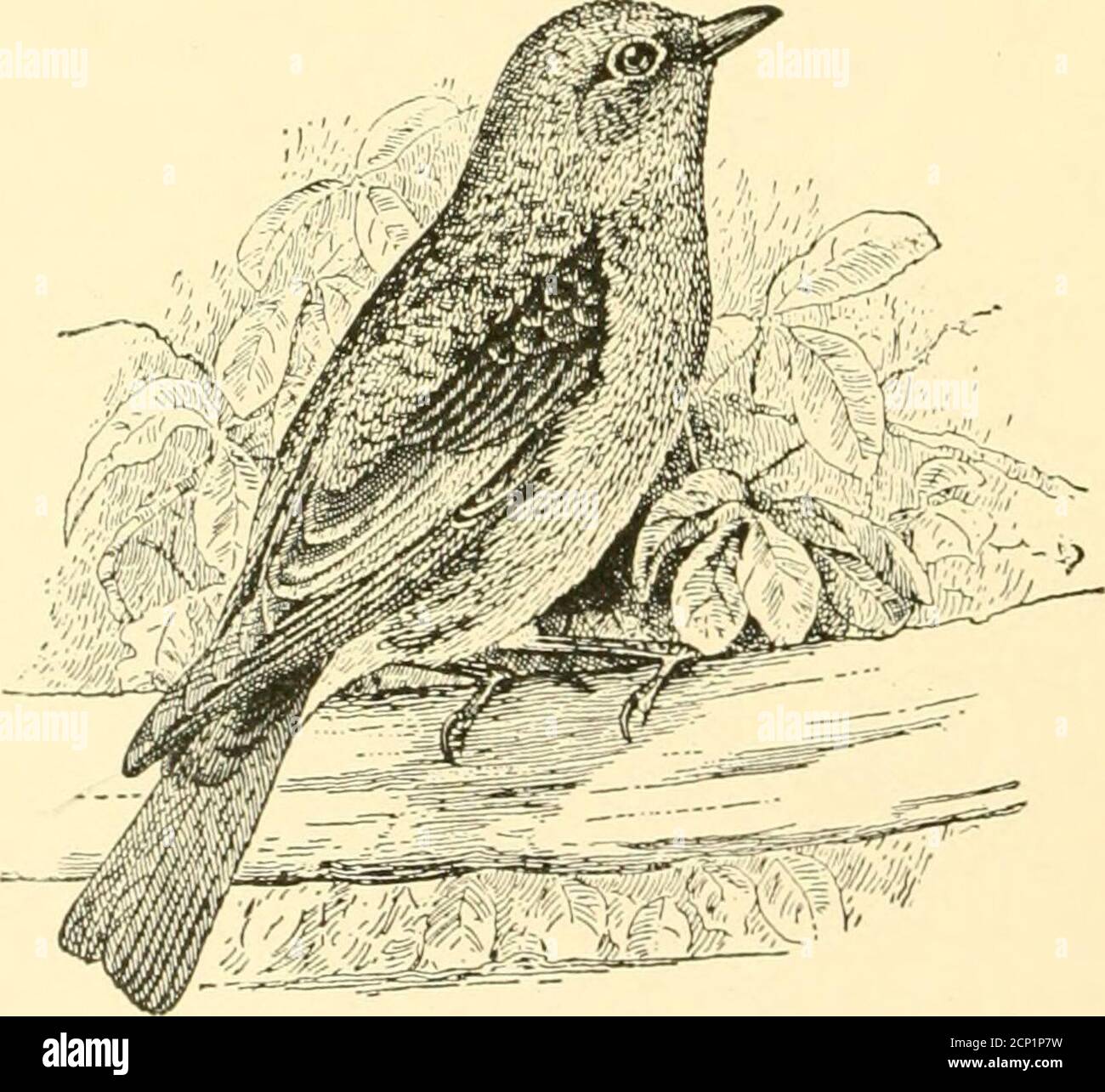

. Birds in their relations to man; a manual of economic ornithology for the United States and Canada . rd usually does harmrather than good in eating a parasite of an injurious phy-tophagous insect. Nothing has been said in regard to those parasites uponparasites which are called the secondary or hyper-parasitesof noxious insects. Our knowledge of the precise biologicalrelations of these is limited. On general principles it is prob-able that when a bird eats one of these it is at least as likelyto be doing man a benefit as an injury.1 1 For an account of the relations between hymenopterous parasitesand their hosts, see Fiske, The Parasites of the Tent Caterpillar, New Hampshire College Agricultural Exp. Station, Technical Bulletin, No. 6. CHAPTER VIII.THE THRUSHES AND THEIR ALLIES. THE BLUEBIRD. There is, perhaps, no feathered songster which has soendeared itself to the people of the northern United Statesas the bluebird. Clad in modest but beautiful colors, endowedwith a voice of plaintive melody, and familiarly associatingwith man, it is one of the most delightful harbingers of spring.. THE BLUEBIRD.I After Biological Survey.) Its insect-eating habits are well known, for the bird may oftenbe seen flitting from its perch in chase of some passing mothor grasshopper. The food of one hundred and eight Illinoisspecimens, taken in every month of the year except Novem-ber and January, was studied by Professor S. A. Forbes. InFebruary cutworms and ichneumon-flies formed the mostimportant elements of the food, twenty-four per cent, of the Mi THE THRUSHES AND THEIR ALLIES. 87 former and twenty-two per cent, of the latter having beeneaten. The larvge of the two-lined soldier-beetle, a pre-daceous species, had been eaten to the extent of eight percent, and young grasshoppers to the extent of nine per cent.Ground-beetles formed five per cent, of the food, soldier-bugsseven per cent., spiders and crickets each four per cent.The ratios of parasitic and predaceous species were very